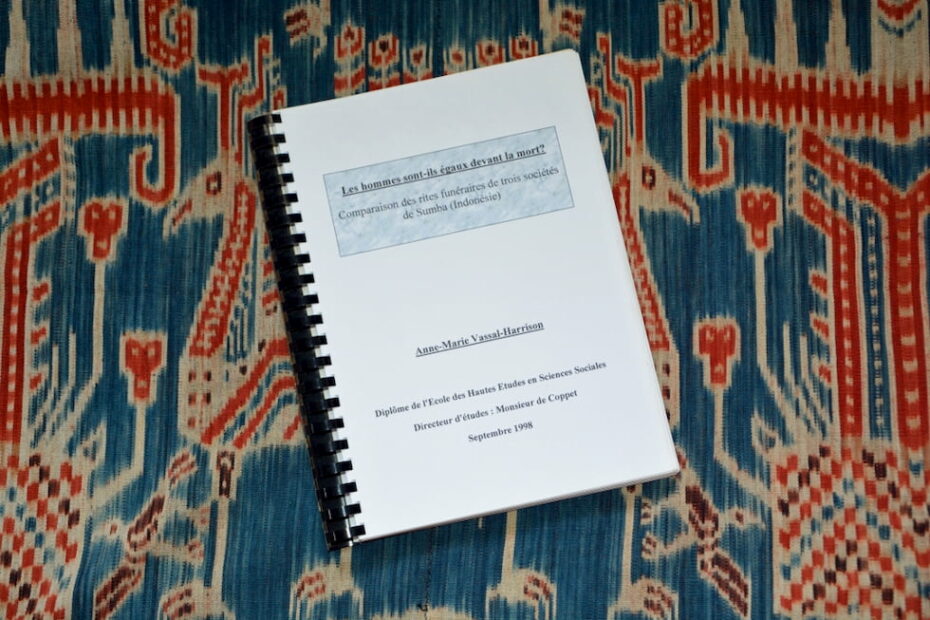

In 1998, I wrote this dissertation to obtain a Diplôme in anthropology (equivalent to an MA) from the École des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris.

I decided to follow this course after returning to Europe, having previously spent 16 years in Asia, during which time I had accumulated a lot of knowledge of the area and worked in museums. I wanted to formalize some of what I had learnt, and I was accepted for this degree course, even though my initial degree from the Sorbonne had been in English.

The subject of my dissertation was “the funerary rites on the island of Sumba”, a topic I chose with the approval of my tutor. I had wanted to choose a larger area than just one small island in Eastern Indonesia, since I had lived in several Southeast Asian countries, but it soon became obvious that it would not allow me to go into the subject in any depth.

The dissertation was written in French but was based on the comparison of three different societies in Sumba which had been the subject of three English studies :

The exact title of the dissertation was “Are all men equal in Death?”. Should you wish to read the whole volume (nearly 200 pages) in French, you would realize that the answer was “no”. In order to spare you this lengthy exercise, I will explain.

In Western societies, nowadays, it is usually thought that any human being has the right to a decent burial, whatever his social or ethnic origin.

This is not always the case in traditional societies: social status is very important to the whole fabric of society, where everybody has a place within the community, which include the ancestors, the dead, and the cosmos. There is a very fine balance that is achieved through the rites that accompany all stages of life and death. Challenging these rights could endanger the whole clan, not just the individual concerned.

What happens to an individual in the afterlife does not depend on whether he has been a “good” or a “bad” person, but how the ancestors will perceive him or her as they enter the realm of the dead: the bigger their tomb, the more lavish the funerary ceremonies have been, the better they will appear and the more pleasant their stay in the afterlife will be. In return, the whole clan will benefit from the good will of the ancestors and will be spared illness, famine and other disasters. In many ways, your fate after death is predestined. People are not equal in life and will remain so after death.